What Allusion Is

- The word allusion comes from the Latin a playing with. Allusions play with a reference from another material source for use in a current writing.

- An allusion is a literary device that makes a brief, passing reference to a real or imaginary place, person, thing, quote, or event found in such items as works of art, literature, folklore, mythologies, historical works, news stories, or religious manuscripts. It’s used in a cursory comment that the writer expects the reader to recognize and understand.

- Many common allusions pop up from Greek Mythology or the Bible.

Common Examples of Allusion

“Twenty dollars! Put the book back, Allison.”

Allison returned the book she’d wanted to buy for her grandmother to the shelf. “You’re such a Scrooge, Lane.”

Miser Scrooge from A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens is the reference.

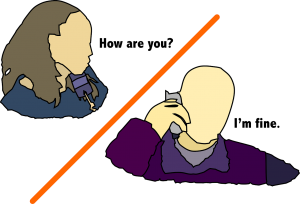

Jackson ended the phone call, dropped his hoe in the garden, and headed for the house. “I’m taking Mrs. Santini to the doctor.”

He didn’t like it, but we called him the Good Samaritan of the family.

The Good Samaritan references a parable Jesus told about a man from Samaria being the only passerby who helped a man who lay beaten and robbed on the side of the road.

Angie opened the box and groaned. Alex knew doughnuts were her Achilles’ heel.

In Greek Mythology, Achilles’ mother dipped him into a river that had special powers to protect him from his foretold early death. But where she held him by his heel was unprotected, and Achilles died from a poisonous arrow shot into his heel—his weak spot.

Why Use Allusion

- Writers use allusions as a ready-made device to describe something or make a point without having to go into lengthy details.

- Allusions can broaden the reader’s understanding of something— connecting emotions or thoughts already associated with the object or event in the allusion to the current object or situation.

- Allusions can simplify complex ideas by boiling them down to a commonly accepted reference.

Caution in Using Allusions

- Allusions depend on the reader’s familiarity with the thing or event referenced, especially from older works of literature. However, if a reader is curious to know the connection, he can easily turn to the Internet.

- Allusions can become overused clichés such as the two below.

A loose cannon.

Cannon’s breaking loose from their moorings on ships of yesteryears during battles or storms and causing damage to the ship or crew is the reference. The phrase often alludes to an out of control person.

It was a dark and stormy night.

The opening phrase of the 1830 novel, Paul Clifford, by Edward Bulwer-Lytton is the reference.

An allusion can make a thing or event easy to understand in few words. Click to tweet.

What’s a common allusion you’ve used in speech or writing?

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts