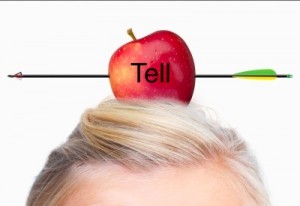

“It’s no wonder that truth is stranger than fiction. Fiction has to make sense.” —Mark Twain

We know exactly what we mean when we write each sentence of our story. We’re surprised when our critique partner or editor doesn’t.

Tweetable

- Does your editor often mark your work with “vague,” “awkward,” or “huh?”? click to tweet

Here are 3 tips that will improve the clearness of your writing.

Tip 1. Huh? That Couldn’t Happen.

When we put phrases in the wrong place or leave out words we can say something that’s impossible.

Example: He’d forgotten to tell Alice he’d seen three wild turkeys playing golf the other day.

Turkeys playing golf? Huh?

Be careful in your rewrite or you may create a new problem. For example: He’d forgotten to tell Alice while playing golf the other day he’d seen three wild turkeys.

Golf-hating Alice played golf with him? Huh?

Better Rewrite: Earlier today, he’d forgotten to tell Alice he’d seen three wild turkeys on the golf course the other day.

Watch out for impossible actions in your writing.

Tip 2. Huh? What does “it” or “that” or “her/him” refer to?

Sometimes we use “it” or “that” or a pronoun that could refer to more than one thing or person.

Example: She gaped. Maude had told Alex every detail about her past. Maude’s blabbermouth would someday get her in trouble. That hurt her now.

Huh? What hurt? Maude’s gossip, Maude’s blabbermouth, or Maude’s ending up in trouble? Whose past was it? [She]’s or Maude’s? And Maude’s blabbermouth would get whom in trouble? [She] or Maude? That hurt whom? [She] or maybe Maude through a tarnished reputation?

Better Rewrite: Amy gaped. Maude had told Alex every detail about Amy’s past. Maude’s blabbermouth would someday get Maude in trouble. Now, Maude’s gossip had destroyed Amy’s chances to marry Alex.

A lot of names. But the reader shouldn’t be confused now. We could revamp the paragraph to cut down some of the names.

Tweetable

- Watch out for the vague “it,” “that,” or pronoun in your writing. click to tweet

Tip 3. Huh? What did that sentence say?

We pack in several pieces of information and end up with a convoluted sentence.

Example: By reaching across the cement wall, Ziggy grabbed the Tiki torch Mom had put there with the hand she’d burned in last night’s fire lighting up the area with it to expose thieves climbing over it, snagging her sweater in the process.

Huh? Who had the burned hand? And did the Tiki torch or the fire light up the area to expose thieves? Did thieves climb over the wall, the fire, or the Tiki torch? Who snagged her sweater?

Better Rewrite: Ziggy eyed the Tiki torch Mom had put near the wall to expose thieves entering the yard. She reached the hand she’d burned in last night’s fire across the cement wall and grabbed the torch, snagging her sweater in the process.

Tweetable

- Watch out for convoluted, awkward sentences in your writing. click to tweet

What other tips do you have to help writers keep their writing clear?

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts